The wartime adventures of the merchant aircrews of Britain's Empire and "G'' class flying boats were no less exciting or less dangerous than those of their Coastal Command colleagues. Flying unarmed, often through war zones, they paid a high price for their daring; but their courage was of the highest order, their contribution to victory immeasurably great.

Things started quietly enough, for the transition from peace to war had, at first, little impact on civil flying boat operations. The home base was moved from Southampton to Poole, and special flights were made for the Services. But, on the whole, Imperial Airways' flying boat services continued much as before twice weekly to South Africa and Karachi, once to Kisumu, in Kenya, and three times a week to Singapore, where pilots of the Australian Qantas Empire Airways took over the last stages of the flight to Sydney. Even the experimental transatlantic mail services operated by Cabot and Caribou were continued until the end of September, 1939, when they were due to finish in any case.

|

"G"

class Empire flying boat Golden Hind launching on

the Medway in England on 17 June 1939.

The G class 'boats were firstly converted into long range VIP military aircraft, then used on the West African link to the Horseshoe. Golden Hind was destroyed during a storm in 1954. |

Imperial Airways passed into history, its organisation being combined with that of British Airways to form B.O.A.C. The new Corporation's Empire network suffered a sharp setback when Italy's entry into the war closed the Mediterranean to British ships and civil aircraft. This action had by no means caught B.O.A.C. napping. On the contrary, full plans for keeping open the vital Empire routes had been prepared against just such an emergency, and parties of ground engineers, complete with "spares," were already on their way by sea to Durban, which was to replace beleaguered Britain as the western terminal of the flying boat route to India and Australia. The idea was to join together at Cairo the two Empire routes from Britain to South Africa and Australia, to form a single great horseshoe shaped route linking Durban with Sydney, via East and Central Africa, Khartourn, Cairo, Palestine, Iraq, the Persian Gulf, India, Burma, Siam, and Singapore. Britain was to be connected to the new route by a landplane service through France, French North Africa, across the Sahara Desert and on to Khartourn.

Sixteen Empire 'boats were east or south of Alexandria on 10th June, 1940, and they were immediately diverted to South Africa for operation on the new route. They were joined there by Caledonia, which had been at Corfu, outward bound from Britain. Within only nine days the "Horseshoe" service was being run once weekly in each direction; after six weeks the frequency was doubled, in plenty of time to play a vital communications role in our subsequent campaigns in the Middle East.

Two

other 'boats—Cathay and Clyde—were in the

Mediterranean area on the day that Italy entered the war,

but they managed to get home. Soon afterwards, France

collapsed and the landplane service linking the

"Horseshoe" with Britain had to be abandoned.

The final air link between Britain and her Empire was

broken, and the

only

remaining international services were from Liverpool to

Dublin, Scotland to Sweden, and Poole to Lisbon, this

last route being flown by Champion and Cathay to connect

with Pan American transatlantic "Clipper"

service.

Cathay went onto transatlantic services while Clyde proved the practicability of a flying boat service to West Africa, and as the trans African landplane route over French Colonial possessions could now be re opened to link up with the "Horseshoe" at Cairo, this meant that Britain could be connected again by air with her Dominions and Middle East forces. Clyde was destined to play a major part in establishing that service on a regular basis, but, before doing so, she made the fifth and last transatlantic flight of 1940.

While she was engaged on this, three other Empire 'boats Corinthian, Cassiopeia, and Cooee, were flown out to Africa to reinforce the "Horseshoe" service, using the route as far as Leopoldville. From there, they blazed a 3,500 mile trail over some of the most remote jungles of the Congo, linking up with the "Horseshoe" at Lake Victoria and so laying the groundwork for a new trans African air supply route, which was put into full operation in the summer of 1941 to supplement the northern landplane service.

Never had the inherent advantages of the flying boat been more apparent, for at none of the stopping places on their new routes did any base facilities exist. In most cases, the flying boats were refuelled by hand from drums carried out in hastily commissioned local barges, launches or even dug out canoes, under the direction of one or possibly two B.O.A.C. ground engineers. Their ability to alight anywhere where there was a stretch of sheltered water enabled them to reforge the chain of Empire communications, and pioneer new routes, where landplanes would have been as much use as a pair of roller skates.

Regular flights over the West African route began in October, 1940, operated by Clare and Clyde until 15th February, 1941, when Clyde, at her moorings in Lisbon, fought and lost her last gallant battle, against a hurricane which caused £10,000,000 worth of damage in the city. Britain's choice of flying boats to operate her long distance air services thus paid handsome dividends in wartime.

|

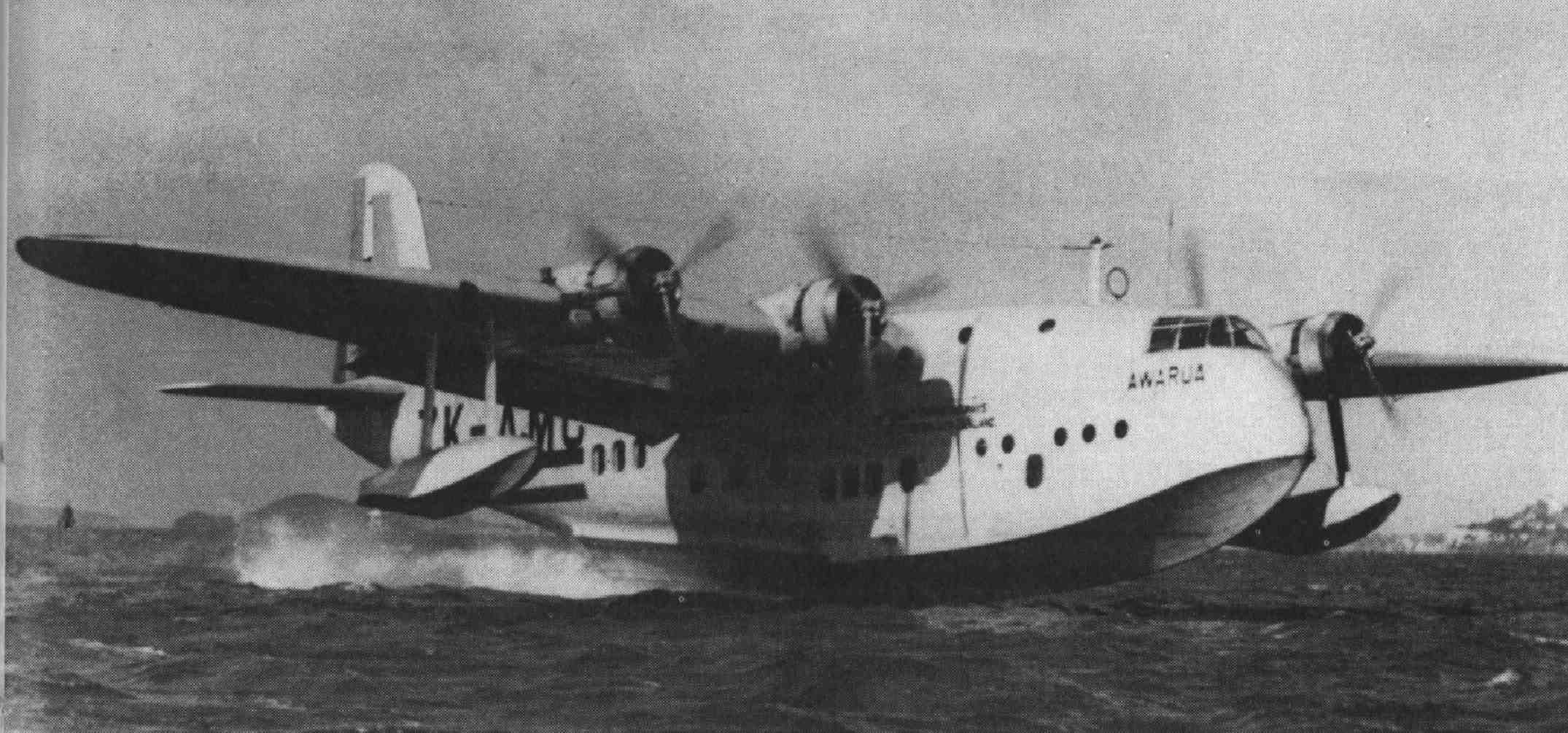

| T.E.A.L. "C" class Awarua lifting off for another Tasman run. |

The

smooth running of the Empire services was threatened,

first in Europe and then in the Middle and Far East, for

1941 and 1942 were years of all out Axis

aggression.

The

"Horse shoe" was broken for the first time by

the German inspired rebellion in Iraq. Fortunately, the

Empire 'boats were at that time in the process of being

fitted with additional fuel tanks, and it was soon

possible to get an emergency shuttle service in operation

direct from Cairo to Bahrein, using the longer range

'boats. They kept the "Horseshoe" intact until

suppression of the Iraqi revolt enabled it to be routed

through Habbaniya once more.

By the autumn of 1941, there was a general improvement in the situation in the Mediterranean and it seemed worth the risk involved to re open the direct flying boat route from Britain to Egypt, via Gibraltar and Malta, avoiding the long detour round West Africa and across the Congo. Clare pioneered the service in October, after which it was flown regularly by five Empire 'boats until the German air onslaught against Malta and Rommel's victories in the Western Desert in the summer of 1942 made the odds against safe arrival too heavy. Then Clare, Champion, and Cathay were switched back to the West African route.

Attempts to supplement them with converted Whitley bombers were unsuccessful, but release of the two surviving "G'' class 'boats Golden Horn and Golden Hind, by the R.A.F. enabled the service to be usefully augmented. Then, one day, Clare disappeared on her way home from Lagos, and it was decided to withdraw the Empire 'boats. But they continued to operate the vitally important Congo route across Africa, carrying supplies destined for the new war zone in the Far East as well as for Egypt.

Meanwhile, Japanese aggression in the Far East had finally broken the "Horseshoe," beyond immediate hope of repair. In anticipation of war, reserve routes had been surveyed in the summer of 1941, but few people had anticipated that the reserves would have to be used within a few days of the outbreak of hostilities. Such was the case, however, as Bankok was occupied on 8th December.

Since October, Qantas crews had taken over the "Horseshoe" service at Karachi instead of Singapore, so the parts of this route menaced by the Japanese were all in their sector. They soon proved themselves no less gallant than their B.O.A.C. colleagues. While doing everything in their power to keep the Karachi Sydney service intact as long as possible, they also flew through some of the most dangerous skies in the world to carry supplies to troops in the front line and to evacuate women and children from threatened areas. Heavy losses were inevitable. Cassiopeia went first on 29th December, while returning from a flight to Singapore with a cargo of urgently needed ammunition. A month later Corio was shot down by seven Japanese Zero fighters, while on her way to collect evacuees from Sourabaya.

After

that, the Darwin Sourabaya route was abandoned, the

flying boats operating instead from Broome on the West

Coast of Australia. Soon even this proved impossible, as

Sourabaya was under almost continuous attack, and plans

were made to fly to Tjilatjap. The situation in Singapore

too was so desperate that the "Horseshoe" now

by passed it and flew through Java. A shuttle service

still ran between Batavia and Singapore at night, but

this was suspended on 6th February, 1942; nine days later

the fortress surrendered.

Simultaneously,

enemy paratroops were reported at Palembang, and orders

were given that no more flying boats were to proceed east

of Calcutta or west of Batavia. The "Horseshoe"

was broken and Australia's air link with Britain severed.

But there was still plenty of work for Qantas' depleted

Empire fleet, to which were added a few B.O.A.C.

'boats that were east of Batavia at the time of the

break.

Qantas continued and increased the supply and rescue missions to the Dutch Indies as long as possible, Circe and Coriolanus taking off for the last flight from Tjilatjap on 28th February. Coriolanus arrived safely; Circe was never seen again and presumably suffered the same fate as Corio.

Meanwhile the enemy had turned their attentions to Australia itself, and Camilla narrowly escaped destruction during an air raid on Darwin. Not long afterwards, Corinna and Centaurus were sunk, together with thirteen other flying boats, mostly belonging to the R.A.A.F., when Japanese fighters made a devastating surprise raid on Broome. Soon only Camilla and Coriolanus remained of the little Australian fleet of Empire 'boats, then Camilla too was lost.

Coriolanus was not, however, alone, for Qantas had by this time acquired a number of ex R.A.A.F. Catalinas. With them they fulfilled in July, 1943, their most cherished ambition, by linking Australia once more with the "Horseshoe." By installing extra fuel tanks, they found that they could squeeze a range of more than 3,500 miles out of these remarkable 'boats, just sufficient to reach Ceylon from Perth in Western Australia. Thus was born the "Route of the Double Sunrise," so called because passengers saw two dawns during the 27 hour flight. They saw precious little else, for the only speck of land along the whole 3,513 mile route consisted of the tiny Cocos Islands!

The magnitude of Qantas' achievement can be gained from the fact that, until the age of modern jet airliners, this stood as the longest non stop over water service ever flown by any airline. Nor did it stop at Ceylon, for Qantas subsequently continued the service up to Karachi, to connect with the "Horseshoe."

| Canopus preparing to depart. The prototype Canopus first flew on 4 July 1936 and went into Imperial Airways trans Mediterranean service on 30 October 1936. |  |

So was built up the broad pattern of British civil flying boat services which contributed so greatly to victory. The "Horseshoe" became one of the most important allied supply lines to India and Burma, supplemented in 1943 by a new fleet of sixteen converted Sunderlands, with which B.O.A.C. flew out vast quantities of war material from Britain to India via the Mediterranean. The West African route was soon required no longer and Empire 'boats from the Congo helped to shuttle ferry pilots from India to Cairo. Champion pioneered a new service to Madagascar, following its occupation by allied forces. Day after day, night after night, all over the world, Britain's civil flying boats played their part until the war was over.

Significantly, the first 'plane to fly into Singapore after its liberation at the end of the war was gallant old Coriolanus. She flew back to Australia loaded to the hatches with happy Australian ex prisoners of war—just a few of the tens of thousands of men and women who will never forget the debt we owe to a handful of flying boats that had been built for peace but achieved high honour in war.

23 Oct 98